There is a global network of airport-based duty-free depots that buy and sell works of art that might never again see the light of day. Chances are you’re not among their customers.

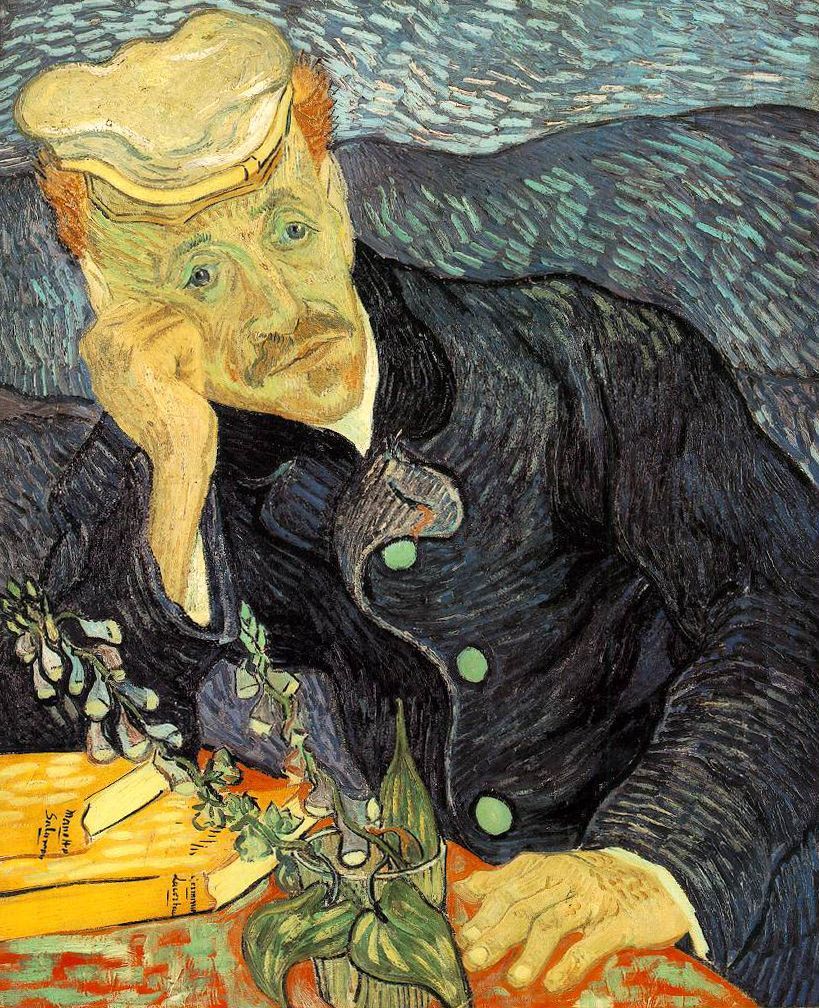

In 1990, Japanese paper magnate and art collector Ryōei Saitō purchased a Van Gogh at a Christie’s auction. He paid 82.5 million US dollars, making “the Portrait of Dr. Gachet” the world’s most expensive painting at that time. Saitō died six years later. In his will, he ordered the portrait to be placed in the coffin along with his body and cremated. Since then, nothing is known about the whereabouts of the masterpiece.

Art in no-man’s-land

International art markets are booming. This often makes speculation on works of art less risky and more profitable than investing in stocks. And a booming international market needs an international infrastructure.

Le Freeport is a 22,000-square-meter storage facility adjacent to Luxembourg’s Findel airport. Around 60% of the space is rented to firms that deal with art. They sell, buy, and store it — all at the free-port zone. According to The Economist, Le Freeport is well equipped to handle works of art. Among others, it features temperature and humidity control and an array of on-site services, such as valuation and renovation.

Additionally, the facility offers wealthy art collectors and traders a triple protection: high security, maximal discretion, and minimal taxes. Works of art that are stored in Le Freeport are exempt from both VAT and customs duty. Art sales that are conducted inside the facility can also be done tax-free.

Free-ports are being used as a long-term storage of wealth and a tax-free space for doing business. There is a network of such warehouses around the world. It’s a fiscal no-man’s-land.

Free-ports are an offshoot of bonded warehouses, where goods in international transit can be stored temporarily without payment of duty. But, increasingly, free-ports are being used as a long-term storage of wealth and a tax-free space for doing business. There is a network of such warehouses around the world. It’s a fiscal no-man’s-land.

But it is also an integral part of the infrastructure of the global capital that occupies the seam between nation-states and their rule of law, widening these cracks.

State authorities are increasingly concerned over their lack of knowledge about what is being stored in free-ports, and who the owners are. The suspicions are that free-ports might be playing an important role in international money laundering and in dealing with stolen goods.

Yves Bouvier is the Luxembourg free-port’s largest investor. Bouvier has also invested in a free-port in Geneva and in Le Freeport’s branch at the international airport of Singapore. “The Freeport King” has recently come under scrutiny for selling works of art — among others, several Rothkos and Picassos — to Russian billionaire Dmitry Rybolovlev for a total amount of 2 billion US dollars. Bouvier was arrested on suspicion of selling the paintings for inflated prices and allegations that some of them had doubtful origins.

Billionaires’ melancholy whims

“I’ve done the portrait of M. Gachet with a melancholy expression. There are modern heads that may perhaps be looked back on with longing a hundred years later,” wrote Vincent van Gogh in a letter to his sister in 1890. He was wrong. Exactly a hundred years later the painting’s fate was sealed and it was doomed to extinction.

The painting’s provenance is intimately intertwined with European history. When National Socialists ruled in Germany, it went through the hands of the Reich’s Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda. They wanted to purge Germany of the so-called “degenerate” art, removed it from the city gallery in Frankfurt and sold it to a private collector.

More often than not, invaluable artifacts of European cultural heritage that are stored in free-ports were never meant to be displayed in living rooms. They increasingly become tenders of global capital and its hostages.

No wonder there was shock and a wave of loud protests surrounding Saitō’s decision to take the portrait of the melancholy head with him to the netherworld. A painting that survived the Nazis is now lost to humanity at the whim of a billionaire.

However, that was a burial of a single painting. A network of free-ports around the world is scaling up the graveyard business. More often than not, invaluable artifacts of European cultural heritage that are stored there were never meant to be displayed in living rooms. They increasingly become tenders of global capital and its hostages.

Forget the Louvre in Paris, forget London’s National Gallery or Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie. The Wall Street Journal estimates that the free-port in Geneva “may house the most valuable art collection in the world.” But, of course, one cannot say for sure which Picassos, Van Goghs, or Monets are in the vaults, as these are, as a rule, secret.